March 25, 2025

Pomona College banned at least 36 5C students from its campus after an Oct. 7, 2024 divestment protest, putting their class credits, jobs and financial aid in jeopardy.

On Oct. 15, 2024, Pomona College began to send out notices to students from Scripps, Pitzer and Harvey Mudd College designating them “persona non grata” and banning them from Pomona’s campus, leaving the students unable to attend classes, work jobs and access resources located at Pomona.

Pomona issued the bans, as well as suspending 12 of its own students, in response to alleged code violations committed during a student demonstration on Oct. 7, 2024 calling for the school to divest from companies supporting the Zionist entity’s ongoing genocide in Gaza.

At least 36 students were initially banned for the full 2024-2025 academic year, though some were eventually able to get their bans lifted or shortened to the fall semester after appealing.

Pomona unilaterally bans students: Provides no initial evidence

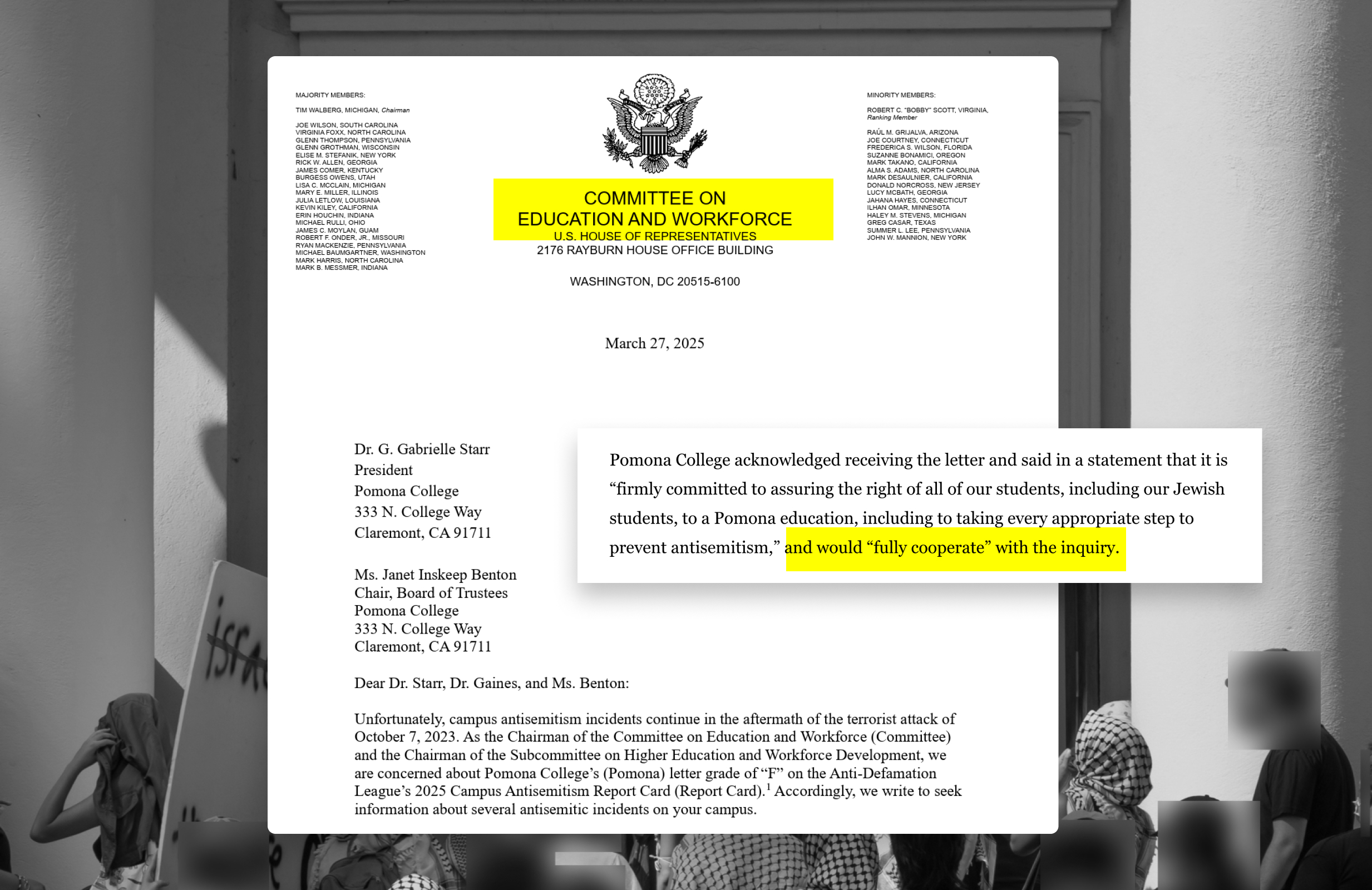

The first group of students received their ban notices in an Oct. 15 email from Pomona President G. Gabrielle Starr, a copy of which was given to Undercurrents anonymously.

“As a result of your presence during the events inside Carnegie Hall on October 7, 2024,” the email read, “you are banned and designated persona non grata from Pomona College…This campus ban prohibits you from entering any and all property of Pomona College…for any reason, 24 hours each day, and will be in effect for the remainder of the 2024-2025 academic year, subject to further review by Pomona College.”

Pomona cited the Banning Disruptive Persons policy as their basis for the bans, though the college administration did not present any evidence of the students violating the Colleges’ demonstration policy, or even of their presence in Carnegie Hall on Oct. 7.

Less than a full page of text, the email did not specify what students were being accused of, but told students, “this ban does not preclude Pomona College from criminal, civil, or restraining action against you.”

The emails were sent out on a rolling basis, with a few ban notices released each week following the initial emails on Oct. 15.

“There was a lot of fear all over all of the campuses, because not everyone was banned on Oct. 15,” one banned student, PZ ’25, said. “They would release a couple more ban letters at the end of every week, which felt like a fear tactic.”

The first emails were sent out at the end of fall break, when many students were still off campus.

“[They wanted] to throw us off our feet as much as possible, and prevent us from being able to kind of figure out what we were doing,” Kate SC ’27, a banned student who requested their last name be omitted, said. “Anything to make sure that we didn’t have access to the resources that we needed.”

Many students felt that Pomona presumed their guilt before initiating the proceedings. Their concerns that the bans seemed confrontational and unjust echo those made about the unilateral power exercised by then-Pomona President Gabi Starr in suspending alleged student protestors.

“You’re not telling me what you’re even accusing me of. I supposedly, allegedly, was in the building,” the banned Pitzer senior said. “Well, how do you know that? You’re not sending photos of me spray painting. It felt like there was no evidence.”

Kate and other banned students similarly expressed concern that no evidence was presented to back up the ban.

“I was like, ‘This is ridiculous. I haven’t been presented with any evidence,’” Kate said.

The initial letter from Pomona offered the chance for students to appeal their bans.

“To do so, please request the modification or exception, in writing, to Dean Avis Hinkson, no later than five business days before the event or activity,” the letter said. “Your request will be reviewed, and you will be notified of the decision within two business days of receipt of your request.”

Despite the lack of evidence backing the accusations, the banned Pitzer senior felt the need to appeal the ban.

“The sanctions and stakes were so high that I had to write some [appeal] letter,” they said. “I mean, I’m a senior. I have so much work, I’m trying to graduate, [but] I had to get pardons from all of my professors and focus for those five days on writing what I felt was like a really good letter.”

Despite the initial email clearly stating Pomona would respond within two business days, Undercurrents is not aware of any banned students who received a response to their appeals from Pomona by this deadline, and many students did not receive a response at all.

The effects of the bans on students were both immediate and lasting. Students with classes at Pomona were unable to attend, ending up with drops and incompletes on their transcripts or struggling to set up independent study with overworked student affairs offices. The ban also revoked access to places of work, 5C campus resources and other community spaces located on Pomona’s campus.

“I did a lot of extracurriculars at Pomona,” said a Pitzer sophomore who was also unable to complete a seminar class at Pomona as a result of their ban.“I do dance and I play soccer at Pomona, so a lot of those things were kind of halted.”

“I don’t even necessarily know where Pomona technically starts [for my ban], like the school library is technically on Pomona campus, but we’re allowed to go there,” the banned PZ ’25 student said, “but [I’m not allowed to go to] the Queer Resource Center.”

Other students were unable to continue campus jobs located on Pomona’s campus, either being fired or unable to attend shifts. Now without income, banned students working at Pomona found it difficult to find new work in the middle of the semester.

Being unable to complete classes at Pomona had an especially damaging impact on students on financial aid. Students receiving financial aid have a limited number of semesters that are covered by their aid packages, meaning that not receiving credit for courses taken could potentially extend their graduation time, resulting in them paying out of pocket for the additional credits they need.

“[Some students are] still figuring out if they’ll be able to graduate because the financial aid covered that semester [but] they weren’t able to finish their classes,” the banned PZ ’25 student said.

The process of appealing their ban, and attempting to communicate with Pomona administrators who continued to ignore them, consumed their semester.

“I was really unwell last semester because the ban process and the disciplinary stuff took over my semester. I was completely not present in my classes,” they said. “I also kept having to miss class to like, meet with a lawyer for advice. It took up so much literal time, and then it was so emotionally and mentally exhausting that I didn’t have the capacity to be a fully active student.”

Second letter sent out to students: Bans potentially extended indefinitely

While banned students waited to hear back on their appeals from Pomona, they received a second email from Starr. Pomona presented evidence this time: timestamps of when students had been connected to Carnegie’s Wi-Fi and alleged images of them.

“You were identified as part of a group of students that entered and then remained in Carnegie Hall on Monday, October 7, 2024, after protesters had taken over the building, disrupting college operations,” the email said. “Based on statements from faculty, staff, and/or students, your actions were egregious and created an environment that endangered the well-being of others.”

The letter went on to say students “broke the trust of our College community and they will have long-lasting implications for members who may never approach students and their teaching/learning spaces in the same way again,” and that their actions had been “exceedingly dangerous.”

“The way that the emails were worded, it just felt very unfair. It was treating it as if all of us had committed vandalism,” the Pitzer sophomore said. “And on top of that, [we were] all painted in the sense that we don’t actually care about other students, we don’t care about learning [and] we don’t care about the needs of others.”

The email contained vague language, initially suggesting the possibility of an indefinite ban.

It told students that Pomona would be “reviewing your response to determine whether this ban should be continued, including your prohibition from continuing in any Pomona courses in which you are enrolled in the fall 2024 semester, and the inability to enroll in Pomona College courses in the future, regardless of modality or location.”

“The second ban letter didn’t actually give us a date as to how long we’d be banned for,” the Pitzer sophomore said. “The first ban letter said that we’d be banned for the academic year, [but] then the second ban letter was like, ‘we actually can’t give you a date at all.’”

Other students felt disrespected and disempowered by the second ban letter being sent without a response to their appeals.

“The response was so disrespectful, it felt like they hadn’t even read [the appeals], right? I don’t think, [they have] to this day,” the PZ ’25 banned student said. “I didn’t have any real power in that interaction to change anything. They had already set their minds as to what the punishment was going to be and offering me the ability to appeal was just like a formality.”

“As a student enrolled in classes at Pomona College, you are subject to the Demonstration Policy and the Banning Policy,” the email said, even though some banned students had never enrolled in courses at Pomona.

“I haven’t taken any classes at Pomona. I never have, and I think that just illustrates how incompetent they are,” Kate said.

The use of timestamps as evidence was additionally dubious, solely based on “connect[ion] to WiFi data via authenticated network connections, which require[s] users to first enter their campus credentials into a username/ password screen,” according to the letter.

For many students, this was all that connected them to the events inside Carnegie.

The Pitzer sophomore, who had been banned based on their connection to the routers, left the protest before other students had entered the building. This discrepancy called into question the validity of the timestamps as evidence, since students could be connected to the routers inside Carnegie from outside the building.

Once again, students were told they could appeal the bans within three days of the letter, promising a response from Pomona three days afterwards. With their major requirements, jobs and financial aid on the line, many banned students submitted second appeals.

“[There] was a common theme,” one PZ ’27 student said. “They would say, like, ‘here’s the deadline, we’re gonna respond to you by then.’ And then they just wouldn’t.”

Kate, like other banned students, followed up with Pomona when the response date administration set for themselves to respond passed, specifically citing the missed deadline.

“You said that you were supposed to respond. It’s been that amount of time and counting. This is ridiculous,’” Kate said. When Pomona did respond, “[Pomona] responded with the nastiest, snarkiest email I’ve ever seen in my entire life, [saying], ‘You know I can’t believe that you would even bother to appeal because you showed no remorse for your horrible actions.’”

Some, like the Pitzer sophomore, were able to appeal following the second email, getting their bans lifted. After appealing, other students’ bans were adjusted to the remainder of the fall semester, though some students have remained banned for the full academic year.

Even for students whose bans have expired or been lifted, the lasting consequences on their jobs, transcripts, graduation requirements and financial aid will continue to stay with them long after this year.

“They were totally silent, which to me, was really loud”: Internal processes at home campuses

As a result of the process of bans and appeals from Pomona, students had to go through internal disciplinary processes with their own school administrations as well.

“Scripps [College] just did not know what they were doing the entire time,” Kate said. “It seemed like Scripps really didn’t want to proceed with the disciplinary process. The administration member that did my disciplinary hearing was like, you know, all of this is kind of ridiculous.”

Scripps’ assistance amounted to offering the help of an administrator in writing Kate’s appeal, and telling her to reach out to Care@Scripps, the college’s student support service.

Kate felt Scripps’ reaction was inadequate in supporting her through proceedings; several banned students at Pitzer College similarly felt like their administrations should have been doing more.

“I felt really disappointed in the Pitzer Administrative Board and their response felt like a lot of silence,” one student said. “I felt like they were totally silent, which to me, was really loud…If your priority was actually your students, you would have immediately stood up to Pomona and said, ‘This is completely unacceptable, you cannot treat my students this way.’”

One banned student from Pitzer explained how they had only been identified in pictures after meeting with Pitzer’s Division of Student Affairs to discuss their initial ban from Pomona.

“They gave me pictures of me in Carnegie, which I’d never seen before, and I asked [Joe Koluder, Assistant Dean of Residential Engagement and Community Standards] where these came from,” they said, talking about their correspondence with Student Affairs. “In all these meetings, I kept asking for the evidence to be able to appeal, and they kept saying, ‘Oh, we don’t have any, like, we’re trying really hard.’”

“[Koluder] told me that they got those pictures in October or November, and so clearly they were lying for months, and then on top of that, they said the way that they identified me was through someone in Student Affairs,” the student continued. “[Which is] just kind of ridiculous, because Student Affairs is supposed to be like, a supportive, safe space.”

The same student went to Pitzer President Strom Thacker’s open office hours to ask him for advice, only to be dismissed and to have the responsibility placed on them for being in an “unsafe situation.”

Student Affairs’ role in identifying the student in images from inside Carnegie, evidence the Colleges only acquired through meetings meant to support them, left them feeling betrayed by Pitzer.

“[Student Affairs is] very explicitly supportive, but they have screwed me over time and time again,” they said.

Students described Pomona’s bans and their own school’s cooperation as punishment for protesting in solidarity with Palestine and an effort to deter further student protests, retributions which their home schools’ administrations were unable or unwilling to prevent.

“[These] schools that really pride themselves on being the antithesis of Trump [end up] being in the exact same camp as him, pretty explicitly and apparently proudly,” one banned student, PZ ’27, said.

Other students were also present and taking photos of student protestors inside Carnegie, which the banned student believed may have been used as evidence.

“They aren’t being punished,” they said. “[But they were] in the building too, right?”

Another banned student emphasized how they were being punished for the collective actions of all student protestors.

“When I’m shown the file of evidence, it is every photo and video from the protest, every photo of every vandalism that was done, every broken anything is on me because I was allegedly in the building,” they said.

“It was incredibly frustrating,” Kate said, discussing her takeaways from the process. “As a student of color, I feel like every attempt I’ve had with dialog with administrations, they’ve already decided that they’re not going to give you what you want.”

The banned students as a whole noted the muting effect that the disciplinary processes have had on demonstrations in solidarity with Palestine at Pomona.

Students suspected of protesting in solidarity with Palestine around the country have continued to be met with retaliation long after their original demonstrations, from both college administrations and, more recently, federal threats to immigration status.

On March 8, 2025, Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian student organizer at Columbia and green card holder, was detained by ICE without charge and moved to a detention center in Louisiana. On March 9, Secretary of State Marco Rubio indicated on social media the government’s intention to revoke Khalil’s green card and deport him.

The crackdown has continued since Khalil, with the Trump administration threatening the visas of all non-citizen scholars showing support for Palestine.

Affinity groups

Palestine

Palestine

Undercurrents reports on labor, Palestine liberation, prison abolition and other community organizing at and around the Claremont Colleges.

Issue 1 / Spring 2023

Setting the Standard

How Pomona workers won a historic $25 minimum wage; a new union in Claremont; Tony Hoang on organizing

Read issue 1